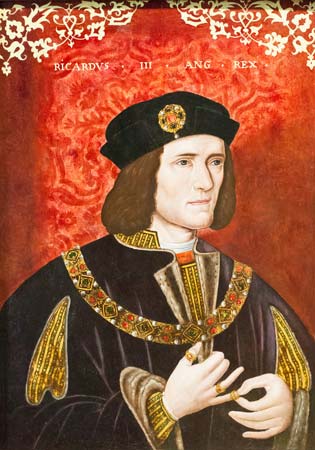

Richard III and the fate of the princes in the tower. It’s a debate that is unlikely to be resolved to satisfaction.

Hard evidence does not exist. We don’t even know for a fact that Edward V and his brother Richard were murdered – let alone at whose hand they met their fate.

But it isn’t true that we know nothing. And what we do have – circumstantial thought it may be – strongly suggests the blame must be laid at Richard’s door.

Here are just seven reasons why.

1. You don’t need to rely on Tudor sources to conclude that Richard’s probably guilty

“Richard’s reputation has been blackened by Tudor propaganda.” It’s a statement we often hear in this debate and is a relatively superficial analysis. It prevents each source being assessed for its individual merit. But it ain’t an argument I’m gonna win with one article.

As luck would have it, I don’t need to. The evidence that points to Richard’s guilt can be found in accounts contemporaneous to his reign. Thanks to the writings of Dominic Mancini and the 3rd continuation of the Croyland Chronicle we have a relatively robust understanding of the chain of events in 1483.

Mancini was an Italian visiting London. He had access to a source close to the Princes and was aware of what information was being put about the capital. We would be unwise to take every word he writes as fact. But the chain of events can be verified by other sources, even though none could have read Mancini’s work. His account lingered in a French library until it was discovered in 1934.

Croyland was almost certainly a state official, though not part of Richard’s inner-circle. Technically it was written in the first few months of Henry VII’s reign. However, it was written too early to be ‘infected’ by ‘Tudor propaganda’. Crucially, it contains information that Henry VII would not have wanted preserved. To dismiss it as a ‘Tudor spin’ would be absurd.

2. Richard killed the Princes most loyal supporters before declaring himself King

Richard’s army of modern-day supporters often argue that Richard’s claim to the crown – based on the supposed illegitimacy of the princes – was widely accepted by the ‘three estates’ of the realm. But surely the fact that Richard had just killed everyone that opposed him and had armies stationed outside London had something to do with that?

Without following due legal process, Richard had William Hastings, a close supporter of Edward IV murdered. He killed – without trial – the Princes’ uncle, Earl Rivers and their half-brother Richard Grey. The message was clear. Resistance to Richard would be met with fatal force.

3. The illegitimacy of the Princes was not accepted

Ricardians also argue that Richard had no motive to have the Princes killed. He had declared them illegitimate and thus they were no threat to him. But Croyland is clear that plots were forming to free them. Clearly, the story hadn’t stuck. Besides, Richard had made them illegitimate by Act of Parliament. Parliament could simply reverse that decision.

4. Richard had the Princes in a high-security prison

Mancini tells us that “all the attendants who had waited upon the King [Edward V] were debarred access to him. He and his brother were withdrawn into the inner departments of the Tower proper, and day by day began to be seen more rarely behind the bars and windows, till at length they ceased to appear altogether.”

While the Tower of London was a royal residence and not just a prison, the boys were kept to a designated area. After a certain point they were not permitted to roam

5. Richard dismissed all the Princes’ attendants and had them guarded by loyal men

Croyland tells us that the Princes were put in the custody of ‘certain persons appointed to that purpose.’ They would have been men Richard trusted greatly.

Occasionally people speculate that these men were bribed by another. But what could they have offered? What could possibly outweigh the benefits to be had from service to the King? And surely these men knew that if they let something happen to the Princes on anyone’s orders but Richard’s they would answer for it with their heads.

6. Richard never accused anyone else of killing the Princes

Richard had the boys in a high security prison. Could anyone – even Buckingham – really have gained access? If they had, Richard would have known about it straight away. Would he really have kept quiet? After all, it would have been a stroke of luck. He could make it clear the boys were dead and pin the murder on someone else. It’s telling that he never did.

7. Richard did not ‘produce’ the boys when doing so would have saved his reign

Some argue that the Princes were never killed at all. I would love to believe that, but it seems unlikely.

In 1485, Richard III faced a great threat from a strange and unlikely coalition. The remnants of Lancaster teamed up with the keenest supporters of Edward IV to topple Richard. If Richard had been able to prove that the boys were still alive, it would have split his opposition down the middle. It might even have united all Yorkist support under him.

But he didn’t. Because they were almost certainly dead.

*

Everything I’ve said here is circumstantial. It’s not categorical proof and I accept that. Maybe it wouldn’t stand up in court. But we’re not lawyers. This isn’t a trial. As Alison Weir says, historians don’t convict beyond all reasonable doubt. They look at the evidence we have and conclude what is most likely to have happened.

So much passion surrounds this debate and it is largely counter-productive. I have no partisan bias against Richard. If new evidence comes to light I would do my best to review it with an open mind.

What puzzles me is that multitudes of Royal History Geeks feel the need to explain away the chain of events that I have outlined above. That Richard ordered the death of the Princes is not the only interpretation of the events of 1483. But surely it is the most likely? I worry that a pre-conceived idea of Richard’s character prevents people from accepting evidence for what it is. This is a dangerous way of doing history. We know so little about the hearts and minds of the people we study.

Henry VII is a king I really admire. I believe he made important shifts in the structures of government which helped pave the way for Parliamentary democracy (which is not to suggest that Henry was in any way a democrat himself). I also think that there is evidence to suggest his character was considerably less blood thirsty than kings that came before or after him.

But I must accept that overwhelming circumstantial evidence suggests that he framed and judicially murdered Edward, Earl of Warwick. The young man had spent much of his life in prison and was probably what we would today consider a vulnerable adult. Whatever Henry’s dynastic reasons for his actions, this was a terrible crime.

Nevertheless, this doesn’t take away from Henry’s achievements as king. Nor does Edward IV’s murder of the old, virtuous and mentally unstable Henry VI diminish his legacy. He showed great skill in managing the nobility and restored order to England. It does make them both three-dimensional characters that need to be studied and analysed. Admired and respected, but never worshipped and revered.

By taking the same approach with Richard, we have a chance to truly redeem his reputation. To rescue him from both his status as unreconstructed monster and revered cult figure. He can finally emerge as the bearer of the broken humanity we all share and the wielder of skills and qualities that deserve to be remembered.

While we’re talking about the Tower of London, we must remember that our wonderful Royal palaces and historical landmarks have taken a real hit during the lockdown. Let’s make sure we get visiting as soon as we’re allowed, to show them our support. Keep an eye on the Historic Royal Palaces website as I’m sure they’ll let us know when doors are open again.

Subscribe to our newsletter!