Introduction

Edward V, and his younger brother Richard, Duke of York were taken into the Tower of London by June 1483. Whether they ever left the indomitable fortress remains an issue of great debate. It is unlikely that this mystery will ever be solved to satisfaction.

Like many students of the late fifteenth century, I believe that the most likely explanation for their disappearance is that they were killed on the orders of their uncle, Richard III. Nevertheless, I am the first to admit that this cannot be proven. I am open to changing my mind and have long been excited about the possibility of new evidence.

So it was with eager anticipation that I poured through the pages of “The Princes in the Tower” by Philippa Langley. The book is incredibly readable. Through a combination of its accessible style and my own interest in the subject, I powered through its 300 pages of narrative and argument in just a few days.

It is a work with real value. The amount of source material that “the Missing Princes Project” (the movement that gave birth to the book) has gathered is beyond impressive. To present it so succinctly is a masterful achievement.

But it is also a work that could have been so much more valuable. The scholarly contribution it could have made is placed in peril by the author’s tendency to force explanations onto sources and require the reader to make epic leaps of logic. Too often, the book’s pages betray its unspoken motive: to prove the innocence of Richard III at any cost.

This review seeks to highlight the book’s virtues. But I have not been shy in drawing attention to the many ways in which it lets itself down.

The Missing Princes Project has attracted global media attention thanks, in part, to a Channel 4 documentary that accompanied the book’s launch. I have long been sceptical about TV’s usefulness as a medium when deep analysis is required. I’m also mindful of its power to stir emotion and create lasting impressions. As such, I decided to read the book and complete the first draft of this review before watching the documentary.

Given the length of this post, I have split it into three bite-sized sections – the positives, the problems and the possibilities. Throughout each section, I have assumed reasonable knowledge around the events of the fall of the house of York and the rise of the Tudors. If you are newer to the topic and find that something doesn’t make sense, please feel free to email me: royalhistorygeeks@gmail.com

Gareth Streeter December 2023

Plymouth, Devon

The positives

I make no secret from the outset that this book has given me more to criticise than praise. That does not mean that it or the Missing Princes Project are without merit.

The positives include:

- Successfully challenging assumptions – the events of 1483 are not as clear as any of us would like them to be. Nor are the motivations of the key players. What the book refers to as “the traditional narrative” does contain assumptions and it is right that these are regularly challenged and robustly tested. The work does a good job of reminding us how little we know about many of the key events. Good questions emerge from the project’s efforts to challenge received wisdom.

- Well crafted and easy to read – the book is compelling and accessible in its presentation. It’s a long book and I was able to read it in days, despite being a slow reader and having only recently checked out of hospital. Given the density of information and arguments it contains, this is a real achievement.

- Based on a interesting and innovative approach – Langley’s attempts to mobilise people to head to their local records office to dig up any relevant records is commendable. In this case, it does not seem that much strictly new material has been discovered, but were such a strategy pursued more broadly, it could help unlock a plethora of the past’s secrets.

- A useful compendium – the team of researchers has gathered countless sources, and the book provides an incredibly useful appendix. This makes it easier to assess the source information and encourages informed debate. For those interested in the fate of the Princes, the appendix alone justifies the cover price.

The problems

The problems with the book do not take away from the positives. However, they do risk undermining the overall credibility of the “Missing Princes Project”.

I have broken down my major criticisms into five areas.

1) Source criticism

This is the biggest area of weakness throughout the book’s pages. I’ve created a spin-off blog post delving into this area specifically for those who would like to read more. But examples of the book’s weak handling of sources include:

- The book justifies its claim that the princes were widely regarded to have lived through Richard III’s reign by pointing to fragmented sources that have far more logical explanations than those the author settles on.

- For example, Langley points to two payment records (one in late 1484 and one in early 1485) that refer to “the Lord Bastard”. While most historians (given the context of those records) take these to be a reference to John of Gloucester, Richard III’s illegitimate son, Langley claims this is not possible. John was not a peer. And as such, Langley claims, would not have been referred to as “Lord”. Instead, she argues, they are more likely to be a reference to Edward V who (she believes) was still regarded as Earl of March and Pembroke.

- But household records show that an illegitimate and untitled son of Edward IV was referred to as “My Lord, the bastard” in 1472. So there’s no reason why John of Gloucester could not have been similarly styled.

- Langley offers the discovery of a payment record, which indicates Margaret of York (Dowager Duchess of Burgundy) was championing “a son of King Edward” in 1487, as irrefutable proof that at least one of the boys survived the tower. But those familiar with such receipts will know that details peripheral to the document’s core purpose (of acknowledging receipt of goods and payment) are often incorrect. And even if it was believed in Burgundy that Margaret was championing a surviving Edward V, that hardly makes it true.

- The unfinished and confused writings of Bernard André are used to further justify the theory of Edward V’s survival. The poet claims that someone masquerading as a son of Edward IV was lurking in Ireland in 1487 (ahead of the Battle of Stoke later this year). But the poet seemed to believe that it was the younger son of Edward IV that was being impersonated making it far more likely that he was confusing events with the later Perkin Warbeck campaign.

- These are just three examples of times that the book fails to scrutinise sources in order to fit them into a preexisting narrative. It makes it hard to trust any of the later treatment of material in the book.

2) Sweeping assumptions and shaky foundations

As the chapters progress, the author proceeds to make sweeping assumptions based on forced interpretations from fragmented evidence.

As stated above, Langley – at odds with most historians – claims that two references to “the Lord Bastard” in Richard III’s reign refer to Edward V. Based on this and a couple of other fragments of similarly distorted evidence, she concludes that the survival of the Princes was well known in England. It is not presented as a question, a possibility or even a likelihood. For Langley it is a fact and for the rest of the book it is treated as such. As the pages progress, it forms a shaky foundation for other theories.

She follows the same approach with the discovered receipt in from the Lille record, the only genuinely new piece of evidence unearthed from the Missing Princes Project. This intriguing find could have been used to question assumptions about Lambert Simnel, the Earl of Warwick and the Battle of Stoke. Instead, it is treated as irrefutable evidence that Edward V survived to 1487. Again, this is accepted as fact for the remainder of the book leading to hugely circular arguments in later chapters.

Such sweeping assumptions continue throughout the book. Langley spends much of Chapter 10 analysing details of Henry VII’s travel itinerary after the battle of Bosworth. The fact he delayed his entry to London, she seems to suggest, shows that he must have deliberately lingered so as to investigate the fate of Edward IV’s sons. (Yet, she does also concede that he needed to ensure a display of victory across the North and the Midlands.)

Without any real explanation, she proceeds to detail the people that “we may assume” were high on the King’s list to interrogate. The author ultimately judges that he either (a) found nothing; or (b) discovered information that he quickly suppressed. Quite extraordinarily, she takes all of this as evidence that the Princes must have been alive.

3) A persistent naivety to the realpolitik of medieval society

The book persistently presumes that fifteenth-century power brokers were simplistically legalistic. The Princes were no threat the Richard III, it argues, because Parliament had stripped both boys of their inheritance rights. But they became a threat to Henry VII because the Tudor King reversed Richard’s Act of Parliament.

This simply does not stack up. Even the most basic review of fifteenth-century history shows how easily such Parliamentary decrees were disregarded. To name just a handful:

- Henry IV’s Parliament left the throne exclusively to his descendants. This did not prevent the house of York from ultimately toppling them from power.

- Edward IV had been declared legally devoid of inheritance rights by Parliament. But “might made right” when he won the crown in battle.

- Henry VII’s Parliament declared that the throne belonged exclusively to himself and his descendants. This did not prevent him from living in fear of pretenders for much of his reign.

An Act of Parliament did not convey the certainty that Langley’s book suggests. The author also makes the puzzling assumption that, by acquiescing to Richard III’s assumption of the throne, the political class must have accepted the intellectual basis for it, including the illegitimacy of the Princes. If this was the case, why, just two years later, were they prepared to accept precisely the opposite?

4) Inconsistent methodology

Throughout the book, Langley admirably encourages the reader to challenge all their assumptions. Yet, in going to an extreme in some situations, she risks entirely ignoring the context of events. Elizabeth Woodville’s decision to flee to sanctuary in 1483, the book argues, should not be taken as a sign that she believed she had anything to fear from Richard. Sources that claim such motivation were written after Richard was King. As such, they are inferring from hindsight.

This is fine as far as it goes. But to suggest that we should ignore “what happened next” when it may provide clues as to people’s motivations is fatally flawed.

Interestingly, Langley seems more prepared to interpret people’s actions in light of future events when doing so supports her theories. For example, she uses events from later in the 1480s to assume a distrust between Henry VII and Sir Edward Woodville after the battle of Bosworth.

The book also only factors in past behaviour when such an analysis supports her theory. Let’s look again at the example of Elizabeth Woodville’s escape to sanctuary in 1483. We can speculate intelligently about the widowed Queen’s motivation by reflecting on the only past occasion where she sought sanctuary. Previously, she had taken to the safety of the abbey when the government had been seized by men hostile to her family. As historians, we have to at least entertain the possibility that her behaviour in 1483 was motivated by similar concerns.

While reflections from the past are ignored in this case, Langley is happy to pluck examples from history when they support the book’s premise. She revisits the reign of Henry IV to highlight the treatment of that King’s rival child claimants, the Earl of March and his brother. This, Langley argues, provides a template for the survival of rival claimants, despite the huge difference in circumstances to the 1480s. She also fails to mention a crucial difference between the March boys and Edward IV’s sons: the survival of the former is well documented. The continuing existence of the latter is not.

But the biggest methodological inconsistency is the different treatment that specific sources receive. Those that support the book’s theories are hardly questioned. Those that challenge the author’s theories are routinely dismissed. As we have seen, the book records that Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy believed she was championing Edward V in 1487 (which is possible though not probable). The duchess later supported a man claiming to be Richard, Duke of York in the 1490s (which is unarguable). Both claims are taken at face value. If Margaret said it, it must be true.

There is an almost dramatic irony about this. Langley and fellow Ricardian researchers are usually the first to call the motives and biases of all figures of power into question. They rightly ensure that every word uttered by supporters of the Tudors is treated with suspicion. But they take a much more trusting approach with the Tudor’s enemies.

5) The methodology itself is flawed

The Missing Princes Project claims to be based on a “cold case” police investigation. This is certainly an intriguing premise. Its PR potential is magnificent and it has drawn more attention to the question of the Princes in the Tower than anything in the last decade.

But does it lead to good history?

In the early pages of the book, Langley draws the available fragments of what we know of both boys together. She then creates a “profile” of each of the Princes. Evidence, claims and theories are later weighed against these profiles.

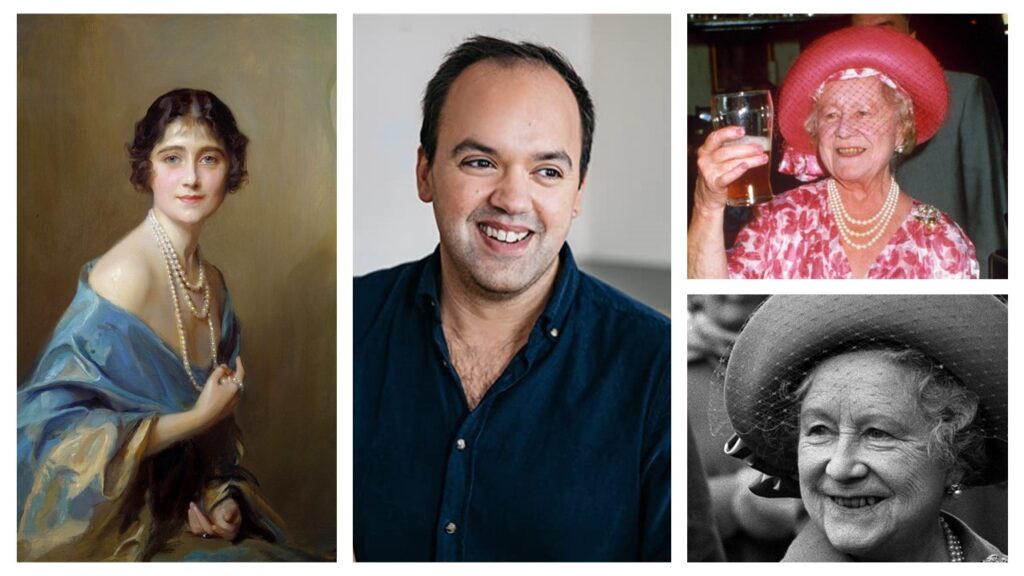

There’s a problem with this approach. We simply don’t know enough about either boy to construct a meaningful profile. Recently, I spent a year researching and writing a book about Prince Arthur. Yet I still would not be comfortable creating a profile of the boy that could serve the robust needs of a police investigation. However hard historians of this era work, and whatever new evidence emerges, we will never have the opportunity to interview people who knew our subjects personally. Nor can we entirely trust accounts of their personality, gifts or intelligence.

The investigation also places a great emphasis on dismissing hindsight. There’s real value in this. It encourages us to think about what we can really glean from the events themselves. However, taken to its extreme, it causes Langley to entirely dismiss a number of contemporary and near-contemporary accounts. She makes the assumption that these writers were all influenced by later situations, when they could well have formed their views as events were unfolding.

The possibilities

The team behind the Missing Princes Project has devoted endless hours to trawling the archives of Europe for any hints about the boy’s fate. From what I can see, only one of the sources is strictly new. However, their efforts to compile information and expose sources to scrutiny has the potential to make the project an activity of scholarly significance.

If the project was able to present its findings dispassionately and release itself from the unspoken pressure of proving Richard’s innocence, their work could make the following meaningful contributions to the debate:

- The fate of the Princes was a mystery from day one – a variety of sources show that during Richard III’s reign and the early years of Tudor rule, there was no clear consensus around what had befallen the Princes. Sources suggest that opinion differed in England as to whether they had perished, were being kept alive within the realm or had escaped custody and possibly the country. We can’t say how popular or widespread any of these viewpoints were, but each seems to have existed.

- The acceptance of a Tudor “propaganda campaign” must be seriously questioned – defending the Tudors may not be high on the team’s priority list but it could emerge as a valid conclusion. The book effectively shows that there was no clear consensus among supporters of Henry VII as to the Princes’ fate. While many assumed their death, there was no agreement around the means of their demise. This argues against an orchestrated, government-sponsored narrative.

- Much of what we know about the Battle of Stoke is based on government sources – building on the work of Matthew Lewis, Langley draws attention to the fact that much of our understanding of the “Yorkist rebellion” of 1487 comes from government sources or chroniclers that enjoyed Tudor patronage. This does not deprive those sources of all value. It does require us to handle them with caution.

- There may have been some ambiguity around who the Irish and Burgundians believed they were fighting for at Stoke (and who Henry believed he was fighting against) – the uncovered receipt from the Lille archives does not, as the book claims, prove that Edward V still lived in 1487. But, when combined with the curiousness of Henry VII’s treatment of Elizabeth Woodville and her son, the Marquess of Dorset, it could lead to a credible suggestion that there was some confusion, at least at some stage in the campaign, as to who Henry VII thought his enemy was claiming to be. There is a great deal of evidence that he and other commentators believed the young boy in Ireland was claiming to be Warwick. That does not mean that this was a view they held with total clarity. It could also be the case that Margaret of Burgundy encouraged a degree of ambiguity in order to keep her options open. And of course, we should not discount the possibility that some confusion arose simply because Edward V and the Earl of Warwick shared the same name.

Such insights may appear modest. They are not. They deserve further investigation and have the potential to change the way that history books are written. The continual quest to vindicate Richard, however, it likely to distract from the project’s positive potential.

Conclusion

I have been captivated by the last decades of the fifteenth century for many years. I am far from alone in that passion. Anyone who shares my obsession will benefit from buying this book.

The appendix alone boasts a wealth of information. The successful and clear compiling of such a collection of documents is a remarkable achievement.

Sadly, that evidence is not well handled across the book’s pages. The author and her contributors fail to scrutinise sources. The wider retelling of events betrays a lack of understanding of late medieval record keeping and the political realities of survival. Far too often, the book makes sweeping assumptions and leaps of logic to justify preconceived ideas.

It is abundantly clear that the Missing Princes Project is pouring endless energy into gathering sources from every corner of the continent. We should commend them for their efforts. They are enjoying even greater success in raising awareness of this perennial mystery. Without a shadow of a doubt, Langley and her team are challenging widespread assumptions about the character and actions of the last Plantagenet King.

Maybe this doesn’t matter. Richard III has a global army of supporters. This book will add a little more fuel to the fire of their arguments. If that’s the purpose of this book, then congratulations! Mission accomplished. And if there are people who are 100% convinced that Richard did away with nephews, and that the bones found in the tower must be the princes (which in my experience, few are) then perhaps this work will give them pause for thought.

But given the huge and (often) high-quality work that has been invested into this project, shouldn’t its aims be higher? Should it not be seeking to make a significant scholarly contribution? One that challenges our perception of the 1480s and causes us to rethink our assumptions? Some of the evidence is this book has the potential to do just that. But that potential remains buried under confirmation bias and an unspoken quest to exonerate a long-dead King.

Philippa Langley is a courageous campaigner. I once (not entirely insincerely) described her as my history hero. She has the spirit of a revolutionary and the charisma of a warlord. But having appeared on TV screens declaring that the reconstructed face of Richard III is not one of a tyrant, she is hardly well placed to be the public face of an independent investigation. After all, the whole premise of the project is that it is based on a police-style cold-case investigation. What law enforcement agency in the democratic world would consent to hand over control of such an investigation to one who has expressed such a partisan interest in the outcome?

Langley has achieved more for her cause than could possibly have been fathomed 20 years ago. The unearthing of Richard III’s remains is the greatest historical discovery of my lifetime. I doubt it will ever be bettered.

But it is now time for Langley to recognise, as so many pioneers before her have accepted, that the passion and determination that has driven efforts this far have now become part of the problem. For the good of the project she has birthed, she should stand aside from its leadership. The torch should be passed to a historian (and not necessarily one with an academic background) that is dispassionate about the outcome and genuinely open minded.

I appreciate that this reads like a devastating criticism of Philippa Langley. It is not intended to be. If anything, it’s a compliment to her charisma and style. Now it is time for her to let the bird she loves fly free from the cage. Only then will she, and the rest of us, discover if it returns to her with the answers she seeks.