Roses, thorns and friendships

1452

I knew I had to stop. Those tingling sensations of vanity were not becoming of a Christian girl. But by Saint George, they felt good.

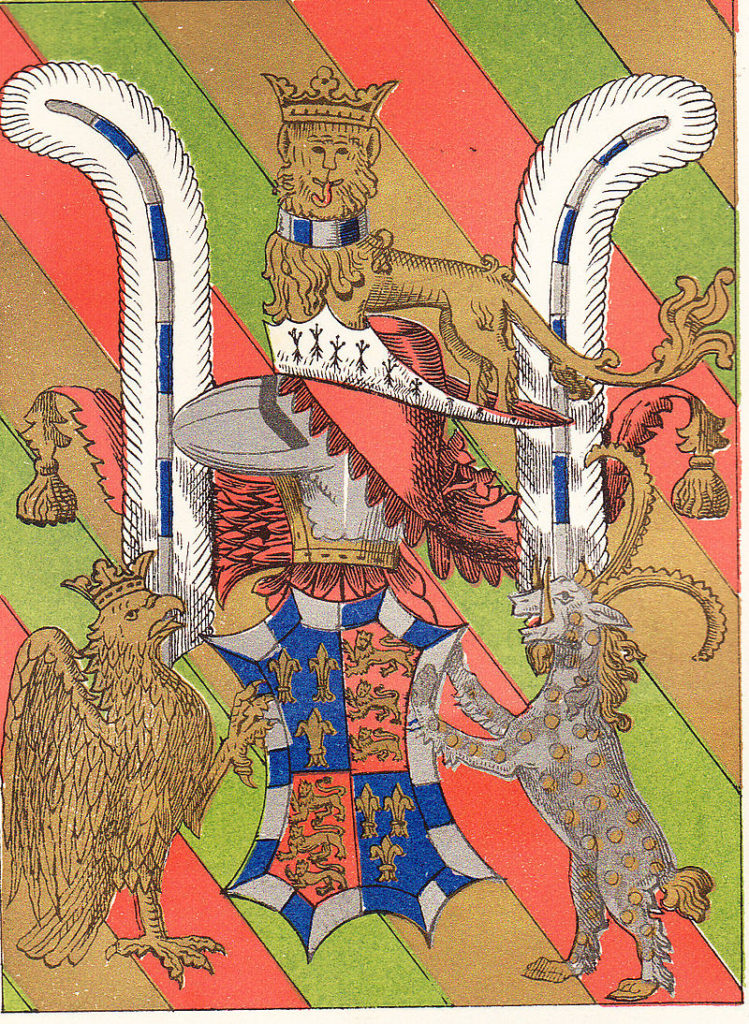

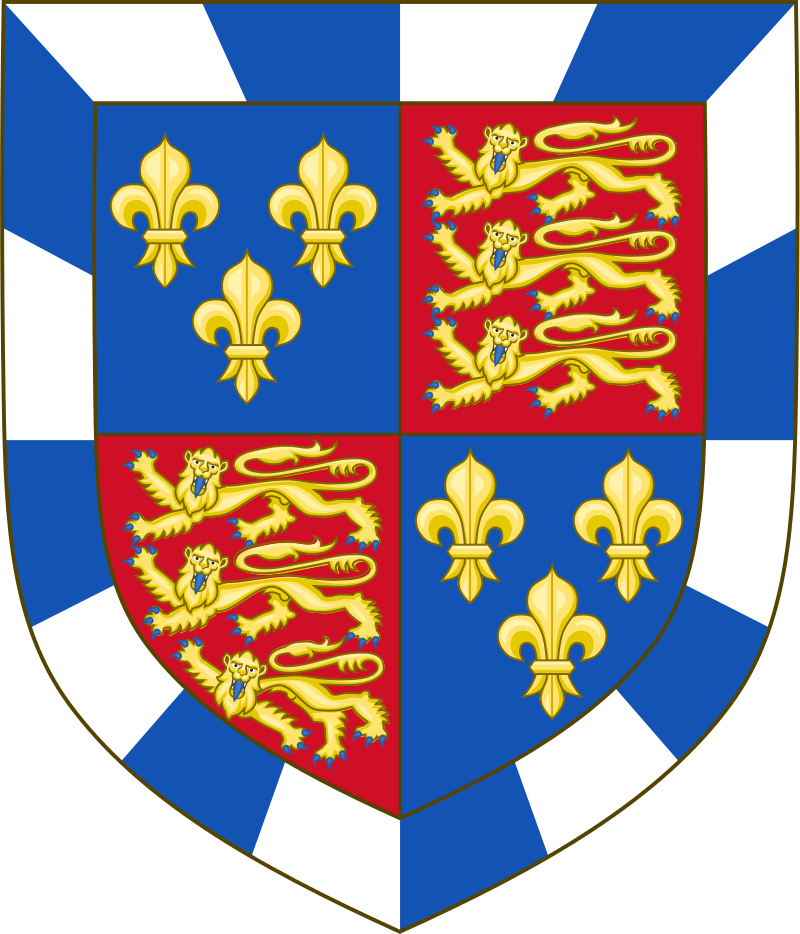

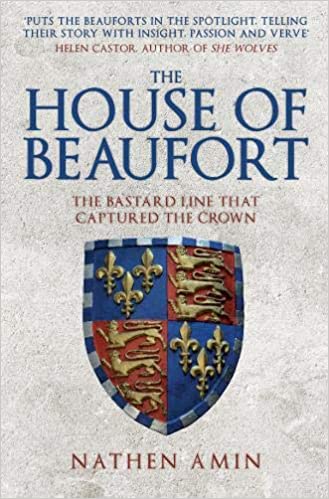

I looked down again at my flowing scarlet gown. With my open sleeves and gold trimmings I felt as radiant as the sun. I had always known I was from a very great dynasty. For the first time, I felt as majestic as the mythical Yale in our family crest.

“Stop it!” I told myself quietly. Like Our Lady, good little girls were to be pious and penitent. But I didn’t want to “stop it”, whatever I told myself. Pride might be a sin, but it was better than that other feeling. That dark, creeping feeling which I couldn’t put into words. It had grown like a weed since we first stepped foot in Westminster, causing lumps to form in my throat and a knot to twist in my belly. If vanity were the only anecdote to that feeling, perhaps the Virgin might understand.

“Now remember Margaret,” mother said, “I will not be with you when you meet the King.” As she spoke she gently lifted my hair, and sprinkled it neatly around my shoulders. Mother revelled in setting my hair. She could never display her own. Wearing your hair loose is the preserve of Queens and virgins.

“Your uncle Somerset will present you. When he does, you will sink into a deep curtsey. The king will come before you and lift you up. Stand there as he talks to you and answer all his questions with the utmost reverence.”

For a minute, mother looked concerned.

“Actually Margaret, there’s a chance the king won’t lift you out of your curtsey. If he doesn’t, just stay there for as long as you can and then gently fall to your knees. In this dress, no one will notice.”

I looked up at mother. No doubt this gentle woman could see the nerves etched on my face.

“Look, you don’t need to worry. The customs at court are not that different to what we do at home when we have important visitors. I like to think you are a well brought up little girl.” She held my face in her hands and gave me a warm, loving smile. “I am confident you will do us proud.”

I trusted mother with my life. And she was right; though I was not quite 10 years old, the customs of court were within my grasp. I was good with grownups and I had already met dukes, bishops, mayors and all kinds of important men. That wasn’t what I was worried about. I wasn’t worried at all.

I was petrified.

No one knew for sure why the King wanted to see me. I was pledged in marriage to his half-brother, Edmund Tudor, a man I had never met. For mother, this was explanation enough. “He’s just curious to set eyes on his new sister-in-law” she had said, almost a little too cheerily. But I knew otherwise.

The King was angry with me.

Before my betrothal to Edmund, I was troth-plight to a boy named John de La Pole. We had met only once but I was under the power of his father, the Duke of Suffolk, who had been my guardian since I was a baby. Father had died when I was an infant and the King, his cousin, had entrusted my welfare to Suffolk. But the Duke was an evil man.

According to Parliament, Suffolk had done something terrible. Criminal! Evil! Mother had no idea that I knew. She probably thought I didn’t even know what ‘Parliament’ was but I’d heard the servants talking. Their words had lingered in my memory ever since.

“Take this linen up to Lady Margaret’s chamber.”

I knew I wasn’t allowed in the laundry room. Or the kitchens. Or the cellar. But I loved seeing how the servants worked, hearing their earthy language and I was small enough to hide in every nook and cranny of our home, Bletsoe Castle. Mother had always said my destiny was be a great lady, running my own house one day. Surely I needed to see how one actually worked?

“Don’t you mean, Queen Margaret,” said the maid who was now in possession of my linen sheets. She fell into a mock curtsey with a girly sneer. Katherine, the older woman who had instructed her, scowled.

“Don’t look at me like that,” the maid defended. “I’m only saying what they’re saying in Parliament. That Duke of Suffolk was going to kill the king and say Lady Margaret was the next in line. She would be Queen. And his son, the King.”

Blessed saints! The Queen. What did she mean, I was next in line? Why would my guardian want to kill the king?

“Now you listen to me,” Katherine was quiet, but her tone as fierce as a beast. “For as long as you want to work in this castle, you mind your tongue. If I catch you talking about anyone in the family like that again, I’ll have a good mind to cut it off for safe keeping.”

The maid blustered a bit. She looked on the verge of mounting a defence.

“I’m serious!” The older lady continued. “You want the Lady Margaret arrested? Beheaded for treason? You go around repeating stories and the next thing we know, people will think they started at this castle and they’ll see truth where there’s none. Is that what you want? Our precious little girl on the receiving end of the King’s anger. The little Lady Somerset dead? And it all on your conscience!”

The younger maid was sobbing. But emotion would grant her no reprieve.

“Linen! Chamber! Now!”

I scurried away as soon as the coast was clear and told no one what I’d heard. But when mother told me that the King had summoned us to court, I knew what it meant. It was time for me to get my comeuppance.

“Your grace,” my uncle said with a bow after I entered the King’s chamber. Mother was outside. Apart from my uncle and two ushers, I was alone with the king. I had imagined the king’s court to be swarming like a beehive. There were countless guards on the outside of the chamber. I have a wild imagination, Mother often upbraids me for it, but I couldn’t let go of the ridiculous notion that the King was like a prisoner.

“May I present my niece, Lady Margaret of Somerset.”

I moved as mother had instructed. I took a few steps so I was lined up to the King’s throne and dropped into a deep curtsey.

For a minute or two nothing happened. With my small legs, I couldn’t hold my curtsey much longer. As mother suggested, I fell to a kneel. My poor, rich garment was unblemished no more.

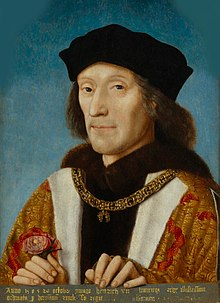

I looked up. Was I meant to look up? I had to see what was going on. Now that I was closer I could see the king clearer. He looked dazed, in some kind of stupor. I had imagined he would wear a crown but on his head was a velvet cap.

“My Lady Margaret of Somerset,” my uncle repeated. He raised his voice and lurched slightly in the king’s direction.

The king looked up slowly. He glanced my way, thought for a minute and smiled. There was a gentleness to his face and kindness in his eyes. Steadily he lifted himself from the throne. He came softly toward me as if he were floating. And then –

Blessed mother! He kneeled. The king kneeled and was crouched down just in front of me. His eyes were wide like a puppy. Now that they were closer, I could see the features on his long oval face. I knew he was a full-grown man, but his face was like a little boy’s.

“Lady Somerset,” he said as he took my hand. His eyes were calm and his touch was gentle. I was used to men like my uncle pulling me and pushing me but the king made me feel like he had all the time in the world.

“We are to be friends. You do want to be my friend don’t you?”

“Oh yes. Yes my lord. Very much.” I panicked. Should I have called him ‘your grace’? Why was he asking this? Were my fears confirmed? Was I here to prove my loyalty and answer for my inadvertent betrayal?

“Oh good,” said the king as he sighed with relief. “I need friends my lady.” He looked sad. For a few moments he said nothing.

“You are my friend so you will marry my brother… I love my brother… then we can all be friends together. We can protect each other and…“ He stopped suddenly. He turned over my hand in his as if to inspect my palm. He reached for my other hand and did the same.

“Lady Somerset, you have brought me no parchment.”

Fear stuck me like a lightning bolt. Here I was, kneeling before the King of England and I had come unprepared. Parchment? I had never thought to bring parchment. Why would I need it? But then what did I know of the court? How could mother have sent me in like this? Why was I not fully prepared?

“I’m sorry y-y-your grace,” I quivered. If he had shouted at me I could have born it. I am used to loud, shouty brothers but gentle disappointment was different. If I had failed him, my heart would break. I was using all my strength to fight back tears. Within seconds, I lost the battle.

“No, no, no my lady,” the king said gently. He lifted a finger to my cheeks and wiped away my tears. Then he cupped my hands in his, “I do not want the parchment but people usually bring it to me. They say if I sign it, it will make them happy. I want to make people happy.”

He paused again. This time for a minute or two.

“However, when I do, my friends get cross with me. William was my friend. He used to get angry with me for signing all the parchment. He said that when I signed it, people would be able to take my money and my land. That they would get jobs which were other people’s jobs. When he was with me, people wouldn’t bring me the parchment. Except sometimes…sometimes William brought me parchment too.

“William said that my real friends wouldn’t bring me parchment.” He grasped my cupped hands tightly, but not roughly. “You must be my real friend.”

I felt relief flood through my body. It was like someone had lit a candle in my chest. For the first time in days, the knot in my belly started to loosen. The king wasn’t trying to punish me. He wanted to be my friend.

“William was my friend for a long time,” the king continued. Tears started to well in his kind eyes. “He used to look after me. But then he had to go away and someone killed him. I did forgive him – the man that killed him. It was very hard but I prayed and the virgin helped me forgive him.”

My heart was breaking as I saw the sadness in this gentle man’s eyes. William must be Suffolk, my old father-in-law. Could he have been so wicked to betray a man that loved him thus?

“Now Edmund is my friend…Edmund is your uncle. He looks after me now….and the Queen. The Queen is my wife. She is beautiful and she helps me.

“And you will be my friend too. I can call you Margaret. Will you call me Henry?”

“Oh yes your gra – Henry.” I was almost laughing with joy. The King was not a strict, brutal ruler. He was a kind, pious, gentle man. And he wanted to be my friend.

“Those of us who are friends have to stick together. Edmund says some people don’t want to be my friend. The Queen says Edmund is right.”

I knew my uncle would be right, he always was. But what a strange notion. The king was clearly a kind man. Why wouldn’t anyone want to be his friend?

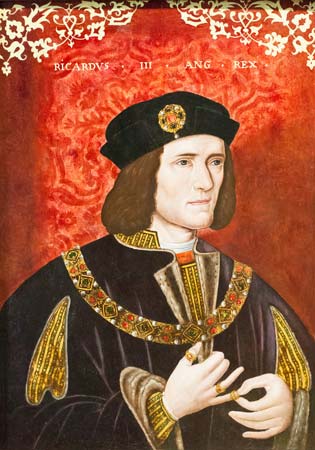

“I have a cousin called Richard,” he lowered his voice slightly. “He is the Duke of York. I like him but Edmund says he doesn’t like me.” He cupped his hand over her ear and whispered. “He wants me to die. He wants to be king.”

I let out an audible gasp. I felt the heat of anger like I’d never felt it before. How could anyone try and kill the King? He was God’s own anointed ruler! A lovely, kind man.

“Edmund says we must work together. He says you will help. He says that you and my brother – he’s called Edmund too – will go and live in Wales and help keep it safe for me. Will you Margaret? Will you be my friend and help me?”

I had never felt more sure of anything.

“Oh yes Henry,” I said at once. “I will always be your friend. I will always help you.” I meant every word. This Duke of York must be a brutal man. A villain. A beast. And if I had anything to do with it, he would never prosper.

Uncle Somerset walked toward us and placed his hand on the king’s shoulder. They must be great friends to enjoy such intimacy.

“Alas my liege, it is time for Margaret to return to her mother. The Duchess awaits her.”

The king looked dazed again. For a moment he looked up at my Uncle before turning his gaze back to me.

“Margaret, before you go, I need to tell you a secret.”

“Of course Henry.” I was a good secret keeper.

“I am scared. When I die, I might go to hell.”

This couldn’t be true. Henry was the most pious man I had ever met, much more than my brothers or my uncle. But fear flowed from his eyes, so I listened with fervour.

“I think God wanted me to be a monk. But I am a king instead. He might be angry with me. I try to be pious. – to hear mass as often as I can. I try and help the church, and in truth,” he again cupped my ear and whispered to me, “I still live like a monk.”

I didn’t know why the last part was a secret. Or what it meant. How could he live like a monk? Monks spent all day in prayer or in study. Henry had to rule. Never the less, my heart went out to him. I had so recently feared punishment for something I had no control over. This great and kind man was tormented by the same fear.

“I will pray for you every day,” I said with fervour. “I believe you to be a good and holy man. You will be upright in God’s eyes.”

The King paused for a moment. He seemed to be pondering something.

“Margaret most of my friends are older than me. When I die, you might be the only one left.”

I didn’t understand.

“I need you to pray for me then. Hold masses. Make sure my soul is protected. Will you do that for me Margaret? You might be the only one.”

“Oh yes Henry. I will pray for your soul with all the devotion of my own. I will lead a blameless life so that God, the virgin and all the saints will hear my prayers. Me and my husband will say mass and pay for more to be held. We will do everything for you. I promise Henry. I promise.”

Within seconds my uncle was leading me out. I had not even been in the king’s presence for half an hour, yet my life had changed forever. My world and my heart had doubled in size.

Only minutes before I was a little girl. My concerns had been for a simple gown and my fears, just of earthly punishment. Now I was a woman with a cause. I was a friend of the King. I must protect him from his enemies and when he finally departed the mortal coil, I would do everything in my power for his soul. This kind, gentle man was a saint, a hero, a champion, and the world needed to know it.

On that day, I found my purpose. I was prepared to devote my life to it.

© Gareth Streeter, 2020